With my colleague Sam Gross, director of the National Registry of Exonerations, I recently published a piece on the 50th anniversary of the Miranda warnings and why so many suspects confess to crimes they haven’t committed, at The Marshall Project.

Here’s an excerpt:

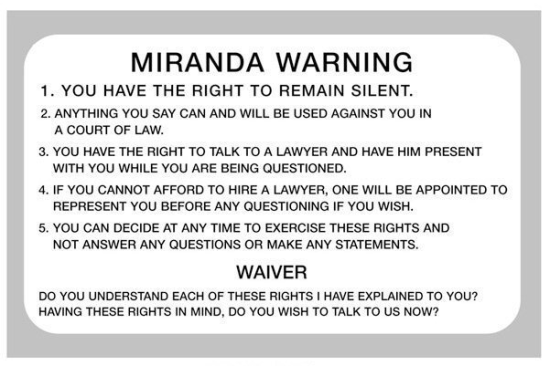

“You have the right to remain silent.”If you’ve ever watched any of the tens of thousands of hours of television devoted to crime dramas, you know the first warning given to suspects who are arrested and questioned. And the second: “Anything you say can and will be used against you.” The Miranda warnings—named for Miranda v. Arizona, the 1966 Supreme Court decision that required them—celebrate their 50th anniversary on June 13. In that period, they have become so ubiquitous that it’s easy to forget their origin and purpose. Miranda was the culmination of 30 years of Supreme Court cases that were designed to protect criminal suspects from abuse in police interrogations. The earliest of these decisions prohibited violence and torture. The first concern was to prevent confessions that are “unreliable”—that is, false.

In 1966, false confessions seemed like a rare problem. Fifty years later, we have seen hundreds of exonerations of innocent defendants who confessed to terrible crimes after they received Miranda warnings.

It’s a good time to take stock.

Do innocent people really confess without torture?Why would an innocent person ever confess to a murder or some other terrible violent crime?

Torture would explain it. That was the issue in Brown v. Mississippi in 1936, the first case in which the Supreme Court excluded a confession from a state court prosecution. Three suspects had been tortured for days. Asked how severely one defendant was whipped, the deputy in charge testified: “Not too much for a Negro; not as much as I would have done if it were left to me.”

Between 1936 and 1966 the use of torture to extract confessions declined greatly, a major accomplishment by American courts and criminal justice reformers. When Miranda was written, a shift was underway to more “modern” methods of interrogation: isolation, deception, manipulation and exhaustion rather than beating. Without torture or threats of death or violence, it seems implausible that an innocent suspect would confess to a serious crime. That is precisely why confessions are such powerful evidence of guilt. But we know it happens, time and again.

The National Registry of Exonerations has collected data on 1,810 exonerations in the United States since 1989 (as of June 7, 2016). They include 227 cases of innocent men and women who confessed, 13 percent of the total, all after receiving Miranda warnings (at least according to the police). Nearly three quarters of those false confessions were homicide cases.

But these exonerations deeply understate the extent of the problem.

Read the article in its entirety HERE.

You must be logged in to post a comment.